Ever since looking at the MIDI Arp, which creates MIDI music based on the network packets travelling over an Ethernet link, I’ve wanted to do something related with Wi-Fi. This is my first try.

Warning! I strongly recommend using old or second hand equipment for your experiments. I am not responsible for any damage to expensive instruments!

These are the key tutorials for the main concepts used in this project:

If you are new to microcontrollers, see the Getting Started pages.

Parts list

- Raspberry Pi Pico.

- Pimoroni Pico Wireless pack.

- Pimoroni Pico Omnibus Dual Expander (optional).

- Raspberry Pi MIDI OUT interface for 3.3V microcontrollers (for example see DIY MIDI Interfaces or Ready-Made MIDI Modules).

- MIDI sound module and amplification as required.

The Circuit

You need to be able to connect both a MIDI OUT interface and the Pimoroni Pico Wireless pack to your Pico, which is why the use of the dual-expander is really helpful.

I’ve used my Raspberry Pi Pico MIDI ‘pack’ Interface and I’m plugging it all into my MT-32 MIDI sound module.

The Code

The original MIDI Arp uses an Ethernet interface in promiscuous mode to “sniff” packets off the wire and use the Internet (IP) addresses of the transactions as the source for MIDI note events. With Wi-Fi I wondered about doing something similar, but there are several issues already:

- You need to be connected – that means logged in – to the Wi-Fi network to ‘see’ packet data.

- I don’t know if the ESP32 used on the Pico Wireless supports promiscuous mode or if it does if it is available from the Pico side of things.

I’m going for simplicity in this first go, so ideally wanted to be able to take advantage of the Pico’s Micropython environment. At the end of the day if I’m going to dig around in Arduino/C/C++ then there isn’t a lot of point using a Pico with a Pico Wireless – at this point I may as well be programming the ESP32 directly and not bother with the Pico at all. I might have a go at a later date with one of my Wemos D1 minis (based on the ESP8266), but that is an experiment for another day.

So I’m using Micropython on the Pico with the Pimoroni “special” version that includes support for all their add-on modules. Details of how to get it up and running can be found here.

To keep it simple I noticed (from the driver files, unfortunately I’ve not been able to find comprehensive documentation) that the Pico Wireless has a start_scan_networks() option.

MicroPython v1.16 on 2021-07-08; Raspberry Pi Pico with RP2040 Type "help()" for more information. >>> import picowireless >>> picowireless.start_scan_networks() 1 >>> picowireless.get_scan_networks() 3 >>>

There are also a series of get_xxx_networks() calls too to pull back various parameters from each of the networks it has found, and sure enough using this in the console shows that it can obtain the names of any Wi-Fi networks it detects.. You provide an index for one of the networks, so in the above example, we’ve found three networks, so we can use 0, 1, or 2 as a parameter to each of these more detailed calls.

>>> picowireless.get_ssid_networks(0) 'MyWiFi\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00' >>> picowireless.get_channel_networks(0) 1 >>> picowireless.get_rssi_networks(0) -47 >>>

So there is a lot of promise here, so I decided to use this information as the basis of some algorithmic music. This has the advantage that you don’t need to log in to any specific network to just scan what is around you.

So how to turn this into MIDI? I used the following scheme:

- Use each Wi-Fi network observed as inspiration for a single “track” of music.

- Use the characters in the SSID as the source of MIDI note numbers for that track.

- Use the Wi-Fi radio channel number (1 to 12) to determine the length of the notes for that track.

- Use the RSSI value as the basis of the note velocity.

To convert from characters in an SSID to MIDI note numbers, I took the ASCII value or each character and mapped the printable ASCII range (32 to 126) onto MIDI note numbers starting from 24 (C1). Conveniently there are 95 printable ASCII characters and 24+95 = 119 which is B8 giving almost 8 octaves of notes. I haven’t looked up the spec of what is permissible to be used in an SSID, so some notes might never show up, but this is fine.

RSSI and note velocity is simple – I take the maximum note velocity (127) and simply add the RSSI value to it as the RSSI is negative. So in the above example, 127+(-47) = 80.

I did wonder about using the Wi-Fi channel number as the MIDI channel number for multi-tracking purposes, but then decided it was more useful as a note length indicator, so I use the channel number as a “count” of “ticks” for which to hold each note on that channel. I’ve opted for a “tick” of one second which means there are potential note changes every second if you have Wi-Fi networks using channel 1.

This seems to generate some pleasingly complicated patterns, especially if there are a good number of networks nearby with interesting names.

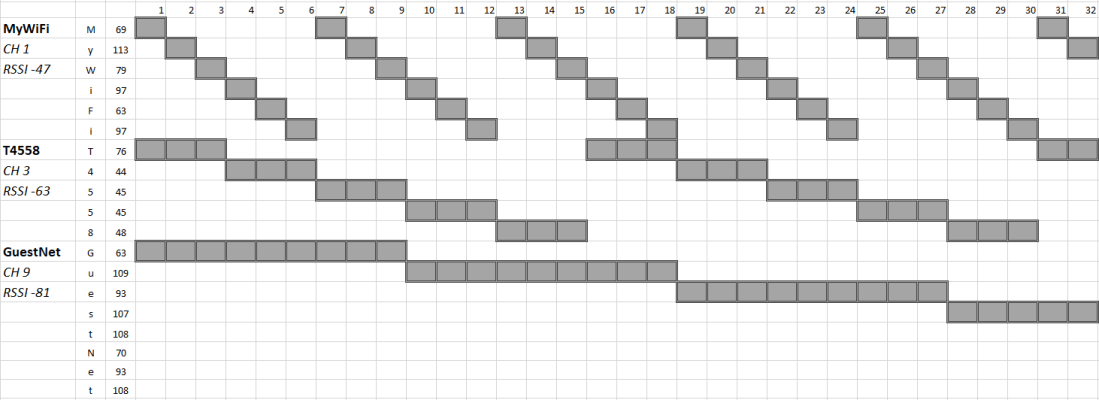

Here is a simple example for three fictional Wi-Fi networks: MyWiFi (channel 1), T4558 (channel 3) and GuestNet (channel 9). Each box division is a “tick” and each line of boxes is one note on a track. The top six lines are track 1 (“MyWiFi” has six characters, so six notes); then track 2 (“T2558”); finally track 3 (“GuestNet”) with 8 notes.

It takes a little while to scan for networks, so I do this every 60 “ticks” (i.e. every minute) which creates a nice pause in the “music” and starts off a new pattern as networks change order in signal strength and appear or disappear.

There is the chance that some notes will be left playing as the Wi-Fi associated with them changes or disappears, but I don’t mind – that adds to the curious effect of the changes occuring.

I’m not going to do a detailed breakdown of the code, but I’ll just briefly describe the key functions.

- scanNetworks() resets all the network related structures and gets new data from the Pico Wireless.

- printNetworks() is a diagnostic function that then prints that all out.

- wifi2midi() takes all the network data and builds the MIDI related structures from it – note sequences, length, volume (velocity), etc. It also initialises two key structures used for playing the sequences – playidx and timecnt.

- ssid2midi() is a helper function to convert from ASCII characters to MIDI notes.

- midiNoteOff() and midiNoteOn() build the MIDI messages and send them.

The main continuous loop has the following logic. Note that timecnt counts up to the length value determined from the Wi-Fi channel number and playidx tells us which note in the MIDI sequence we are on for a specific track we are playing.

Turn the LED ON

FOR EACH network:

Check the timecnt[]. IF triggered THEN:

Turn off last MIDI note playing on this track.

Increment the playidx[] for this track.

Play the new MIDI note for this track.

Turn the LED OFF

Check the rescan counter. IF triggered THEN:

re-scan for networks.

re-build the MIDI data from the network data.

SLEEP for one second

Closing Thoughts

This generates a really pleasing feel. It is particularly interesting when you have several nearby networks sharing the same MIDI channel numbers as that means the note sequences all change at the same time. You can hear it driving the Vibe2 voice of my MT-32 in the above video.

This was the first algorithm I thought to use and I’m really pleased with it, so haven’t tried anything else yet, but there are so many opportunities for variations. I’m also limited at present by what I can see without being connected to a network, and I’m limited by what functions are exposed to Micropython from the ESP32.

As I said at the start, I might increase the sophistication and build something that I can programme from the Arduino environment directly… but I might not. I quite like the “tinkerability” of this version.

I’d really like to build this into a self-contained sound generating unit, then I’d be able to take it for a walk and perhaps listen to the local Wi-Fi environment using headphones.

By the way, I love the, er “vibe”, of the MT-32 Vibe 2 voice being driven like this. It reminds me of some of the “electronic tonalities” from the amazing Bebe and Louis Barron written for the film “The Forbidden Planet“.

Kevin

One thought on “Pico MIDI (H)Arp”